If it was supposed to be different, it would be.

An excerpt from Little Detours and Spiritual Adventures

The writer and monk Thomas Merton wrote that he wished to “disappear into the writing, perhaps it could be a prayer.” That’s what my brother-in-law Tom’s writing -- and his life were -- a prayer.

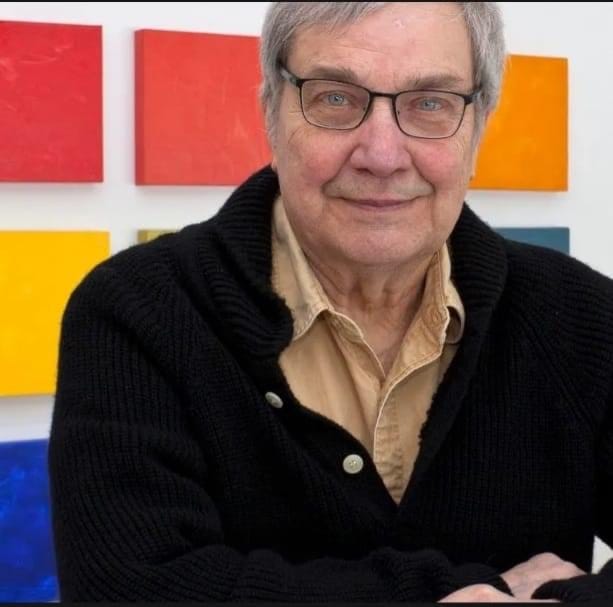

Tom Raithel’s great love was poetry. His wife, my sister Therese, called it his “magnificent obsession.”

I think it was also his church.

Words are so holy, that in the Bible, the book of John starts with this sentence: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.”

Tom practiced the sacrament of writing known to the world as poetry. He loved words and weighed each one with his pen and that brilliant mind of his and that deep heart of his. Each word had to land just the right way on the reader’s heart.

And it did.

Tom didn’t see clouds, he saw “sailboats of gods, climbing and crossing waves of sky; the misty breath of giants / snoring under the rocks and forests, / shaking the world in their sleep.

He saw “flying islands…mirrors of thought, lakes in the sky, / modeling clay for cherubs and angels, airliners filled with traveling dreams.”

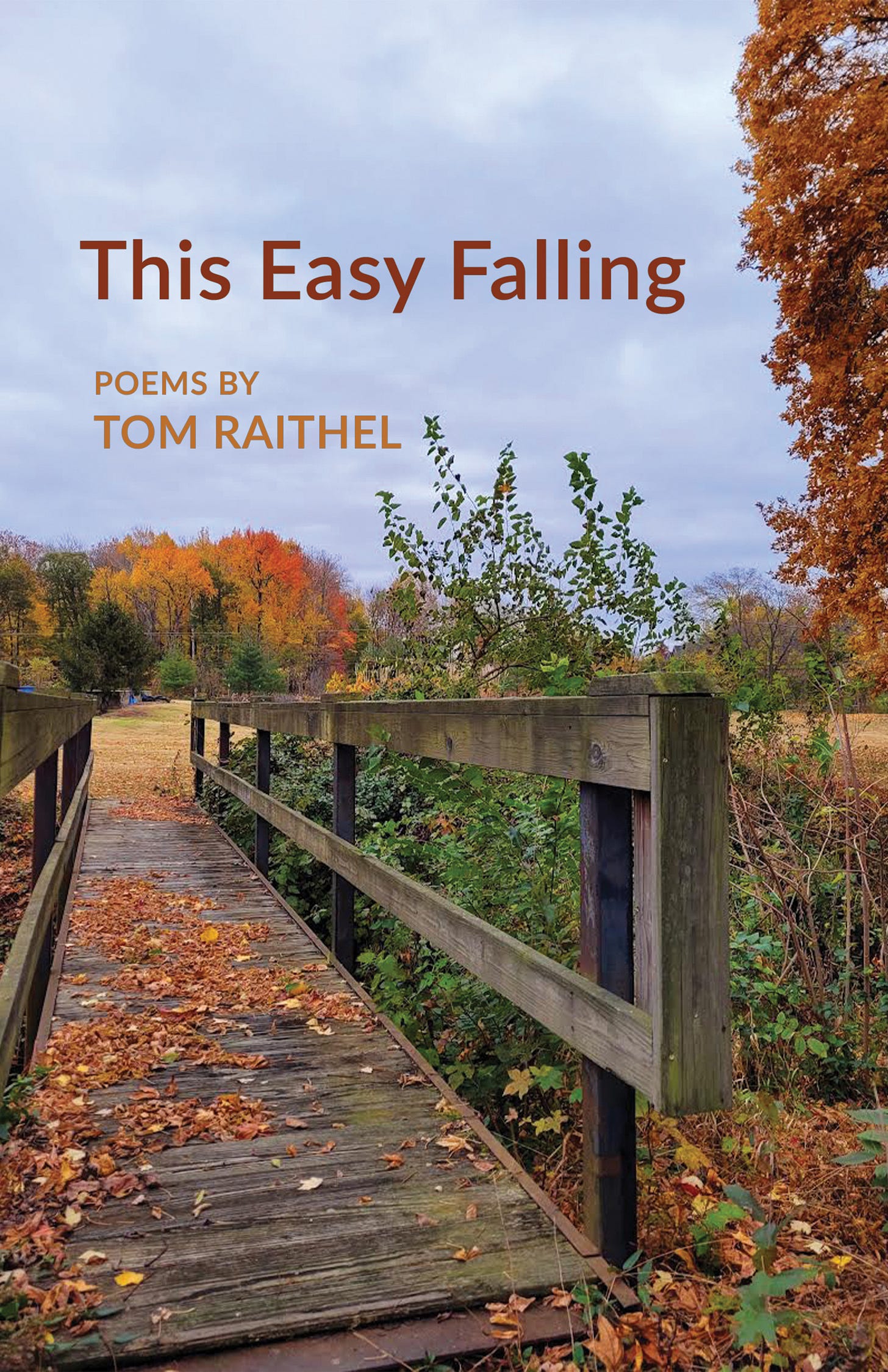

It was hard to get past the irony of the title of his last book, This Easy Falling. Or maybe not.

The saint Julian of Norwich once said: “First the fall, and then the recovery from the fall. Both are the mercy of God.”

Both. Yes, both.

Tom went to Milwaukee to enjoy a weekend with friends and never saw the inside of his home again. But his home was always in words.

He slipped in a hotel shower and broke his neck, leaving him a quadriplegic. Even after the fall that paralyzed him, his words were of gratitude.

He told his wife, “My faith has never been stronger.”

He had the most peaceful look on his face when he told me in Cleveland’s MetroHospital rehab: “I’ve had a really good life. I’m really at peace. I don’t feel I’ve been cheated at all.”

Tom smiled when he took account of what remained: “I have good friendships and family. I’m 71. I have had a pretty full life.”

His new book had not yet come out, so I became his assistant to do the final edits. Tom was such a good writer, I found just one random comma, like a fallen eyelash on the top of a page. Tom had already measured every single word like it mattered -- because each one did to him.

Tom lived to see his book of poetry published. He had the biggest book signing of his life at the nursing home. With that, he completed his life. He loved his wife, his brothers, his extended family and his chosen family, dear friends from childhood and from recovery.

Tom never seemed upset to see a bracelet on his body that read NO CPR. He had embraced life all along. Poetry did that to him, for him.

In all the times we sat in the courtyard at the nursing home, there was no striving for more. He would tilt back his wheelchair and bask in the sun, savoring every ray like it might be his last. He knew.

There’s a saying in recovery: “If the only time you’re talking to God is when you’re in trouble…you’re in trouble.” Tom was never in trouble, even after he fell, because he had a deep spiritual life.

His response to every challenge was almost always a quiet surrender, followed by deep gratitude for what he had, not regret over what he had lost.

Think about that: He drove out to spend a weekend with friends and never returned to the life he created here. He lost his ability to move, to shave himself, to bathe himself, to use a bathroom, to feed himself, to open a book, to go to a baseball game, to drive a car, to play guitar, to get on a plane and see the rest of the world.

In those early days, hope was a moving target. His world became call buttons and catheters, splints and gloves, PT and OT, speech therapy and art therapy, then swelling, spasms and pain.

And yet, his words? Gratitude.

Tom constantly told those who helped him, “You guys are amazing.” I sat with him nearly weekly and never once, never once in 18 months did he ask, “Why me?” Or ask, “Will I ever be able to…” (fill in the blank).

He let the blanks remain blank. Poets know when to be silent.

His silence challenged us all to grow out of the shock and anger and fear. He helped us expand our prayer lives and challenged our ideas of God and mercy and hope.

He helped us grow closer as a family as we all navigated which hospital, which surgery, which rehab, which nursing home. As we sorted out legal and financial and medical issues. As we fretted over which bed to buy, which wheelchair to purchase, which voice recognition software could help him use the TV, the lights, the phone.

All Tom wanted? Those precious moments when we read aloud to him, watched a ballgame, prayed together, called to catch up, shared a laugh, a story or a meeting on Zoom.

In Tom’s beloved recovery fellowship, they often say, “Don’t quit before the miracle happens.” We didn’t get the miracle we all wanted, but we witnessed so many miracle moments, how could we feel shortchanged if Tom didn’t? Like when he brushed his teeth for the first time after the fall, and fed himself, and drove the wheelchair and created a piece of art in therapy as a gift for his wife.

Christians might call Tom’s injury a cross to bear. If that’s true, it’s one we all took turns carrying for a while, one Therese rarely put down.

Or maybe Tom carried us. He showed us how to love the smallness of it all, a song in the Piazza at the nursing home, a scoop of chocolate ice cream, a breeze kissing his face.

Tom recovered from the fall, but not the way any of us wanted him to. We had hoped he would return to writing. I offered to be his assistant and told him I would type out the words for him. He just smiled. He knew the poetry had to flow directly from his head, heart and hands to the page.

I still miss so much about Tom. He came over weekly to walk our dog and always brought his own treats and potty bags. He taught me and my grandson to keep the score at a baseball game by pencil. It forces you to savor every play. We learned the fine art of penciling in a backwards K for those strikeouts where the batter didn’t even swing. We called ourselves the Geek Squad. When my grandkids, Asher, Ainsley and River, made homemade Christmas tree decorations and brought over a small tree, Tom kept it up all year – with the lights on.

I’ll never forget when River brought poems her fourth grade class wrote for Tom. After she read each one by his bedside, Tom took time to praise each one.

Many shared the great gift of recovery in meetings with Tom almost every Saturday on Zoom. I’ll never forget the moment the secretary of the meeting asked, Is anyone willing to sponsor? Tom always wanted to be of service, so from the wheelchair in his bedroom, he lifted his hand.

We didn’t even know he could lift his hand until that moment.

It's comforting to believe that Tom completed his life. In his 41 years of sobriety, he received every single one of the 12 promises his fellowship offered, including these:

We are going to know a new freedom and a new happiness.

We will not regret the past nor wish to shut the door on it.

We will comprehend the word serenity and we will know peace.

No matter how far down the scale we have gone, we will see how our experience can benefit others.

We will intuitively know how to handle situations which used to baffle us.

We will suddenly realize that God is doing for us what we could not do for ourselves.

Tom made his life a poem and a prayer. One that will bless our lives forever.

Such incredibly beautiful writing. Thanks for sharing with us.

You have written about Tom before Regina and I have long since marveled st his incredible courage and saintly attitude. I read about him again after receiving your great new book from Gray Publishers. It was a blessing to be able to put a face to his name! Thank you!❤❤❤🙏🙏🙏❤❤❤